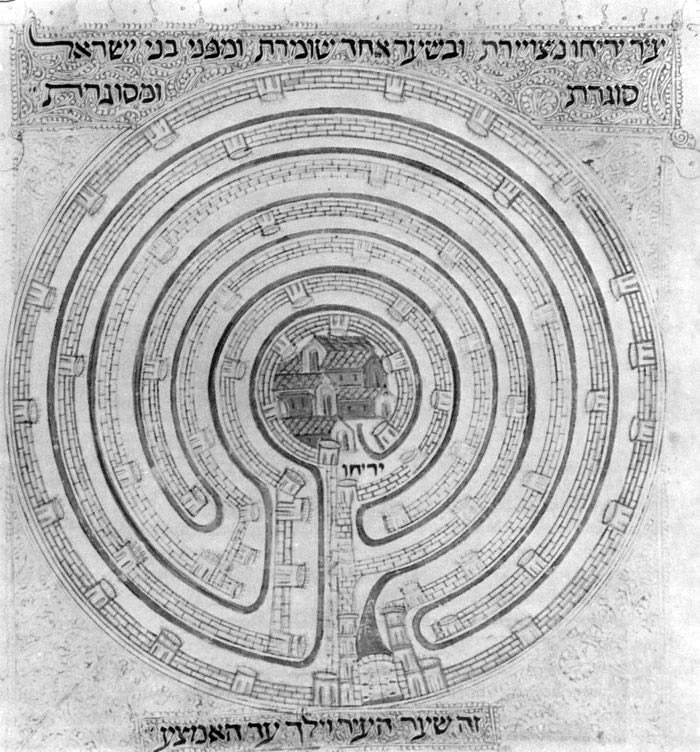

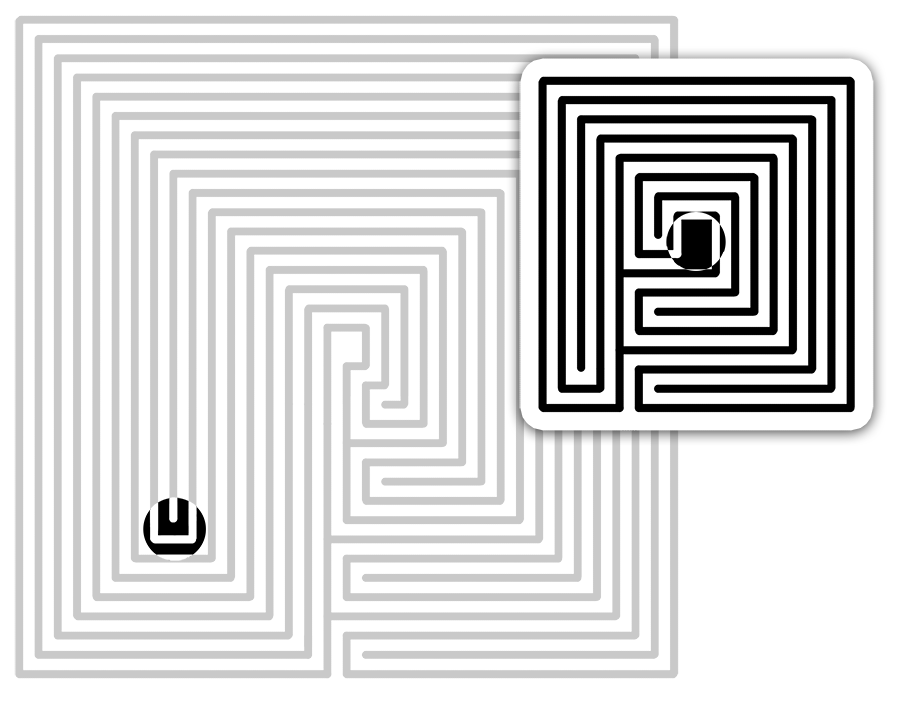

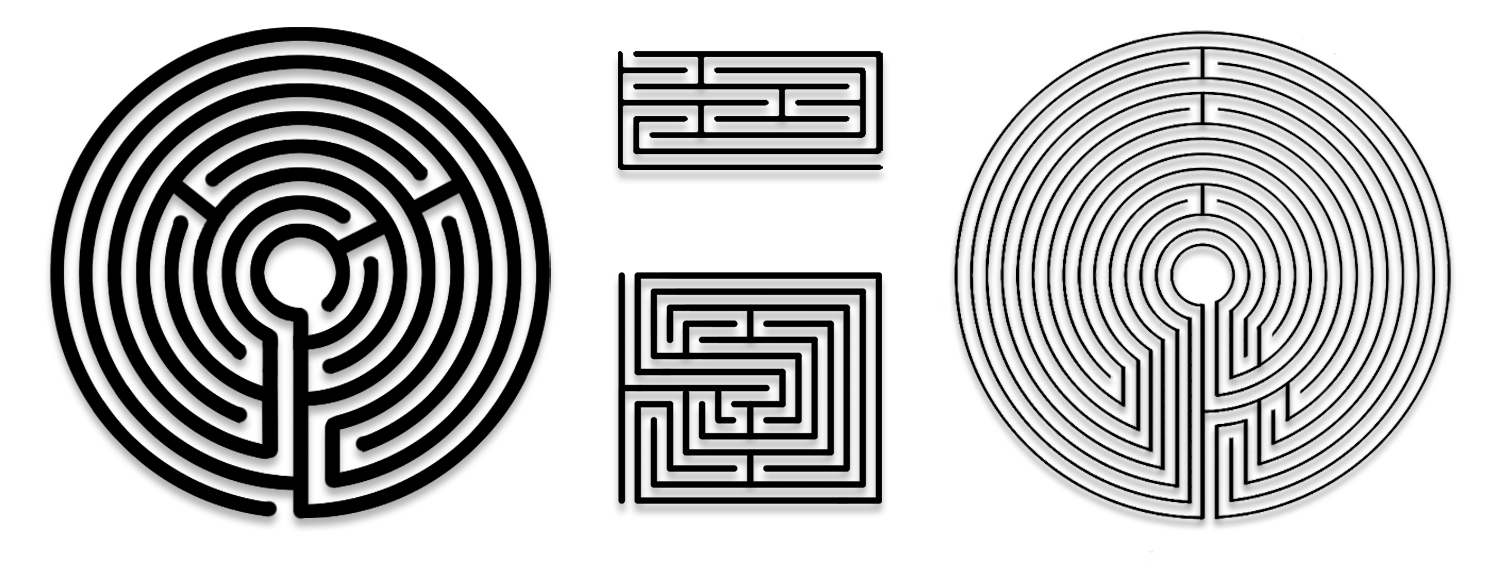

A focus of many Jericho labyrinths is to condense the classical labyrinth’s seven circuits into a six circuit variant, and this may confuse us initially, given that the circumnavigation of a city seven times (as the story requires) should surely, if each traversal is shown as a labyrinth’s circuit, require a seven circuit, eight walled labyrinth – such as the four fold classical of Figure 2. However Kern explains that this visual convention (of six circuits, and seven walls) resulted from a shift in focus over time, such that a wall (rather than a path) came to represent circumambulation: ‘the walls delineated in these illustrations are the material expression of the legendary “compressing” of the city’ [Kern 2000: 128]. [2]

From this artistic licence he concluded that to their creators, the design of the labyrinth was arbitrary and only the sum of walls mattered. I would add to this that the hidden labyrinth property of K227 which we’ll discuss in this article was also very probably an unwitting, chance addition they would not have been aware of.

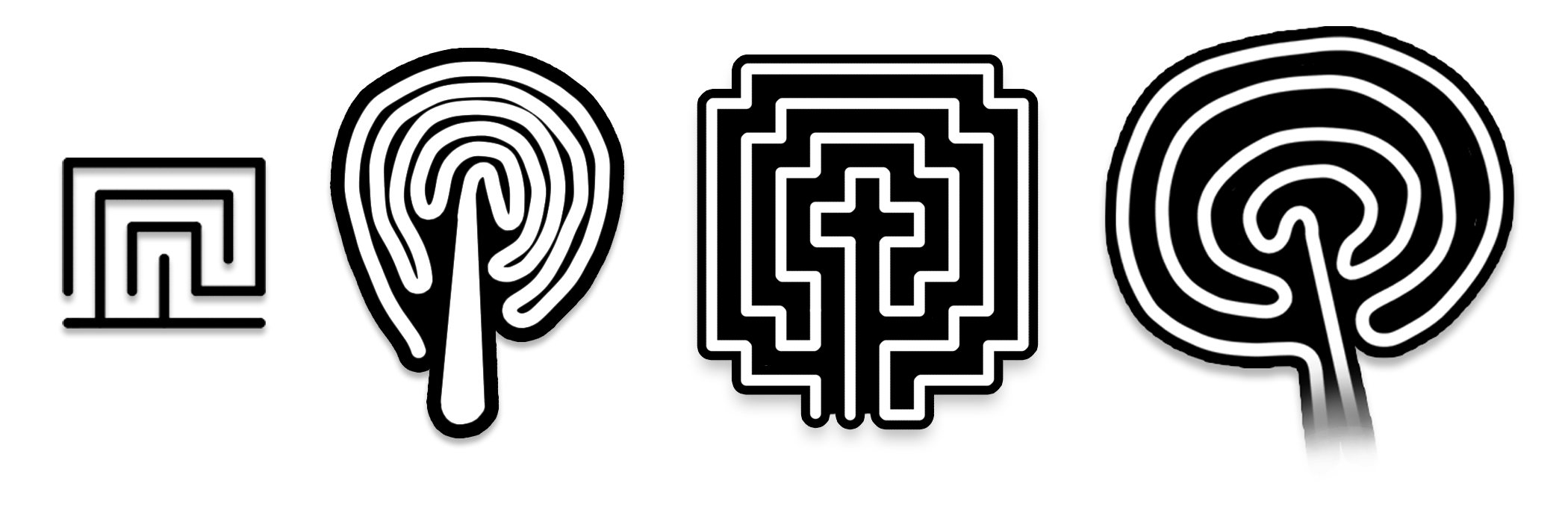

A proto-labyrinth is embedded in the seed pattern of this Jericho labyrinth in Figure 3. By ‘proto-labyrinth’ I mean such patterns as in Figure 4, which – but for their unpronounced pattern-centres and for having a different entrance and exit point – would otherwise meet Kern’s criteria for being a true labyrinth [Kern 2000: 23]. [3]

In Figure 3, if we extract this labyrinth’s compression diagram (CD), rotate that diagram 90° anticlockwise (as shown bottom right of the figure), and then compare this with the labyrinthine patterns of Figure 4 (a Babylonian entrail pattern, a Norman font-carving from the UK noted by Janet Bord, and most well-known, the Nazca pattern), we see these are the same, with start and exit routes merely needing tidying to the sides. Some are slightly larger versions of Figure 3’s CD (e.g. the Nazca pattern, Figure 5) but the same logic of motion creates them.

Of course, this proto-labyrinth pattern and its back-and-forth motion is easy to discover, so it’s no surprise to find its independent appearance in different times and locations. It is an advanced stage along the journey that began with the spiral, and later flowered as a path that fills all space like the spiral between its periphery and centre, culminating in the labyrinth whose path weaves, confuses and alternates direction. At Figure 4 we have almost reached the true labyrinth – except for those separate entrance and exit paths, and their lack of ‘real’ centres, i.e. a middle place usually indicated by either a swelling of path-width, or presenting the sole dead end in the pattern.

Nonetheless, these are familiar patterns to those of us interested in labyrinths, and recognising this proto-labyrinth inside the south axis of a wider ‘parent’ labyrinth suggests the question of whether a true labyrinth could be embedded in that parent’s seed pattern - a labyrinth within a labyrinth. Is this possible?

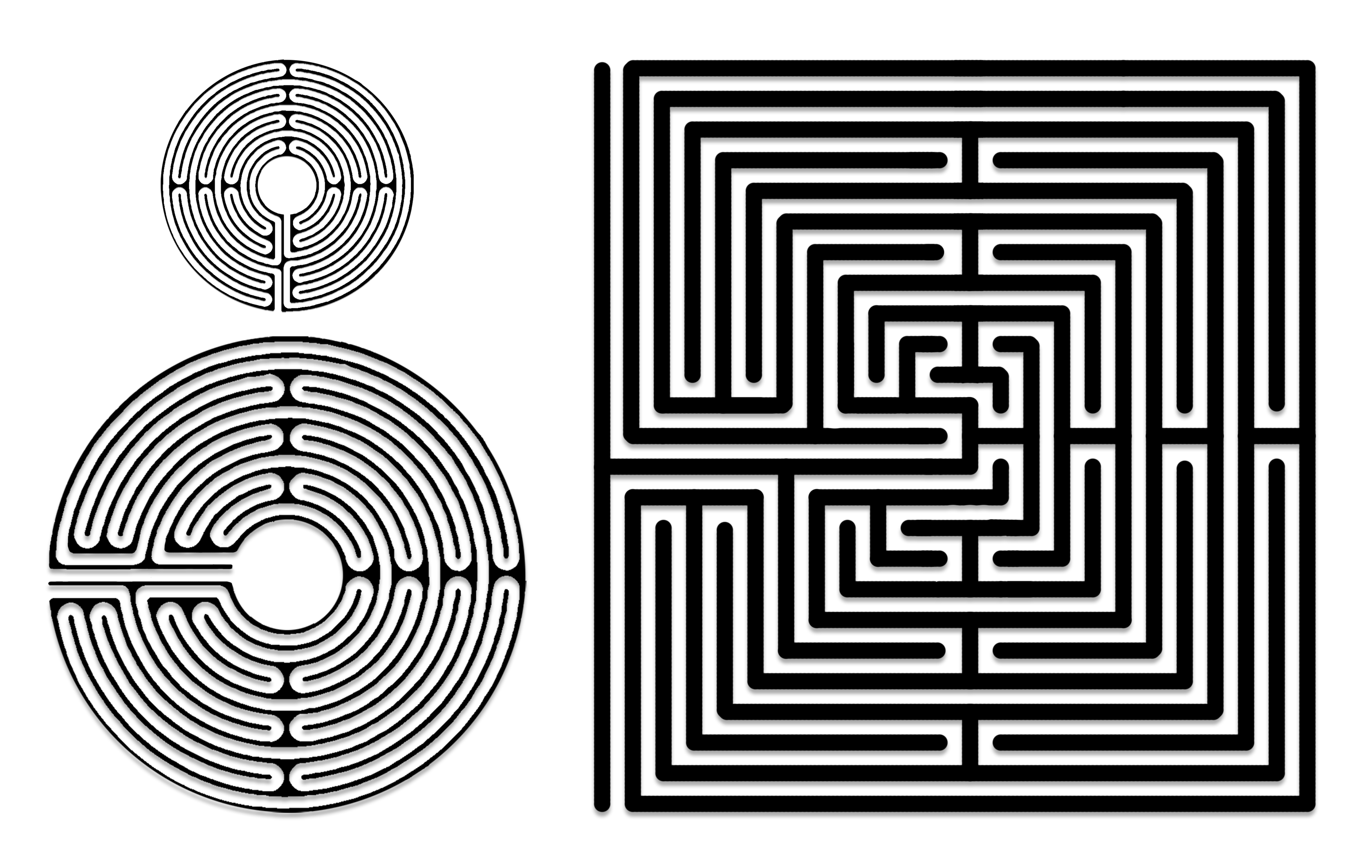

Let’s see, using

the familiar and sufficiently complex patterns of the four fold classical and a

no-frills, Chartrain pattern.

Jericho with Rotated Classical Embedded

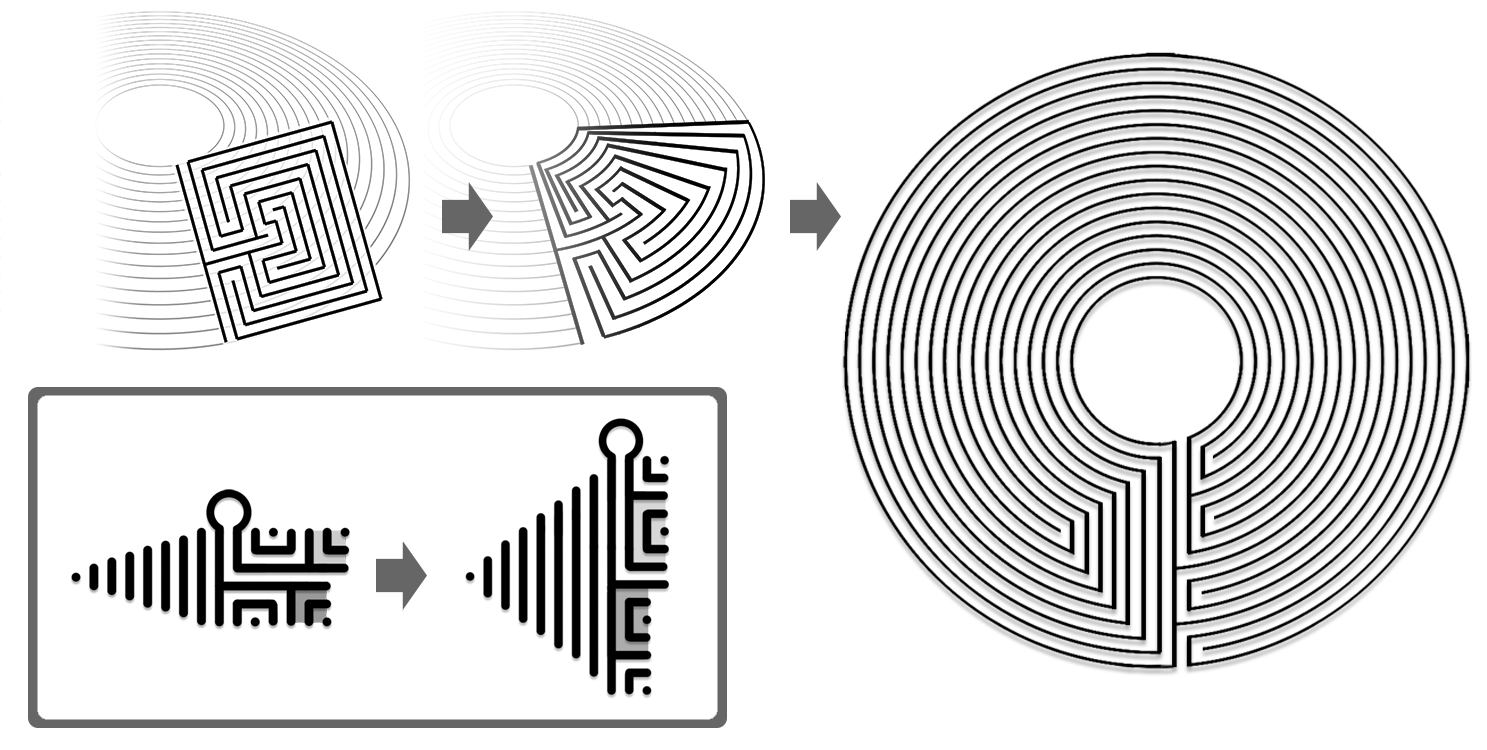

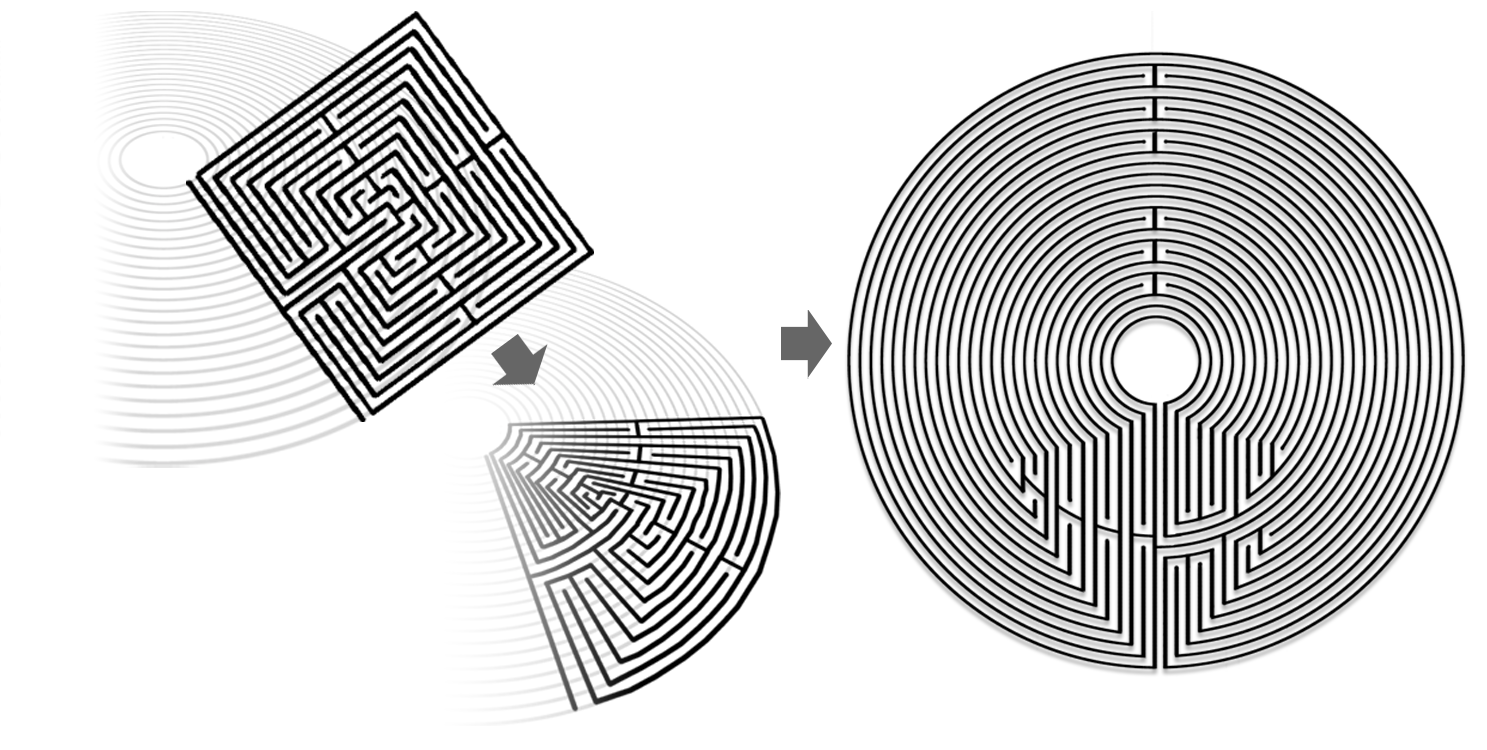

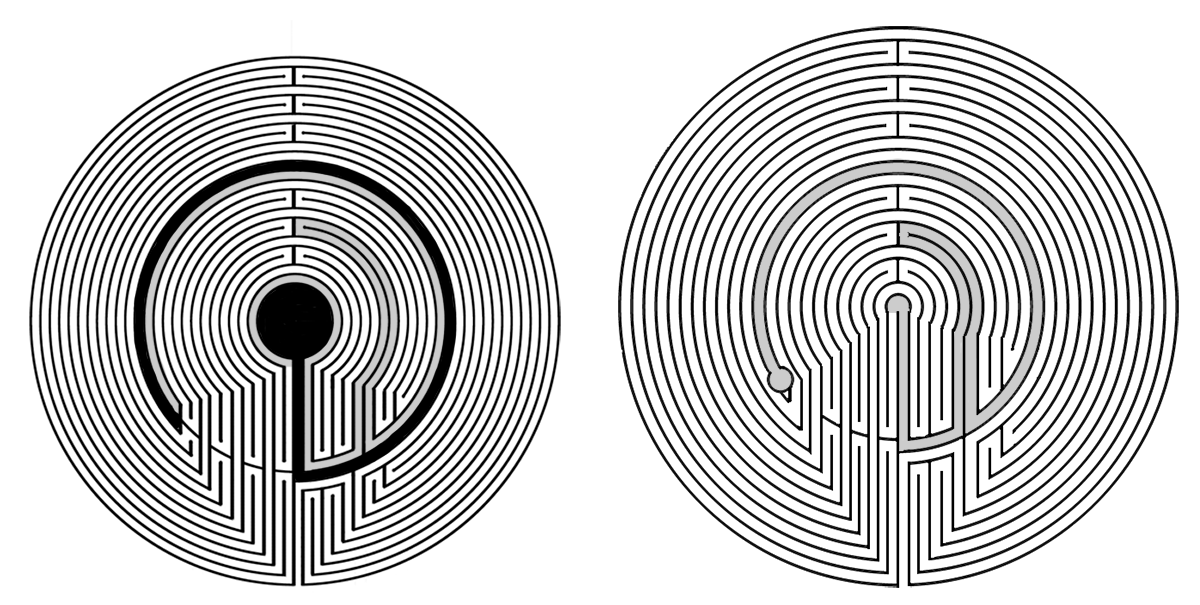

Here is a version embedding a four fold classical (4FC) in the south axis (Figure 6). To create this, we first take a straight-line version of the 4FC, then tilt it 90° clockwise to align with the Jericho’s spine. We must also add to our tilted straight-line 4FC an additional exit route directly from its centre, because our 4FC from its placement in the Jericho south axis must connect the entrance and centre of that parent labyrinth (Figure 7). It is in fact now the CD of our parent labyrinth, and by unfurling its contents across the concentric circuits, and letting our CD’s left- and rightmost edges meet in self-enclosing form, we create our Jericho labyrinth. Note that it’s a big labyrinth, too; we’ve left our motif of travelling seven times around a centre far behind, and henceforth use ‘Jericho’ merely to distinguish this style of labyrinth design.)

Figure 6 was a clunky pattern but in Figure 7 we further simplify its seed so as to be less ‘side-heavy’ (see inset box) by moving the two innermost 4FC folds closer to the south axis; we stack the folds vertically rather than letting them spread horizontally. This isn’t a required step but is noted as a design option; our Jericho will never be a beauty, but is now slightly less asymmetrical to view.

(Which coincidentally brings us momentarily close to the thought-processes of the Roman mosaicist creating that curious 4FC from Nîmes [K151, Figure 8], who was clearly toying with how far the elasticity of the circuits would stretch, and where the centre could be located. It may initially appear a Jericho-esque design after what we’ve looked at so far, but note how differently each pattern places the centre of its ‘holding’ 4FC. Nîmes [inset] although odd-looking with its rejigged plumbing, does have an obvious centre – at, surprise, its centre. However the 4FC embedded in our Jericho [background] has been tilted along the parent labyrinth’s south axis, resulting in its 4FC’s original centre now being found as a flattened lone fold, left of main axis and lost in circuit-swirls.)

So, we have created a Jericho labyrinth that has a 4FC stowed

away within its innards. Our next experiment is even more Frankensteinean; we

repeat with a medieval labyrinth in our seed.

Jericho with Rotated Medieval Embedded

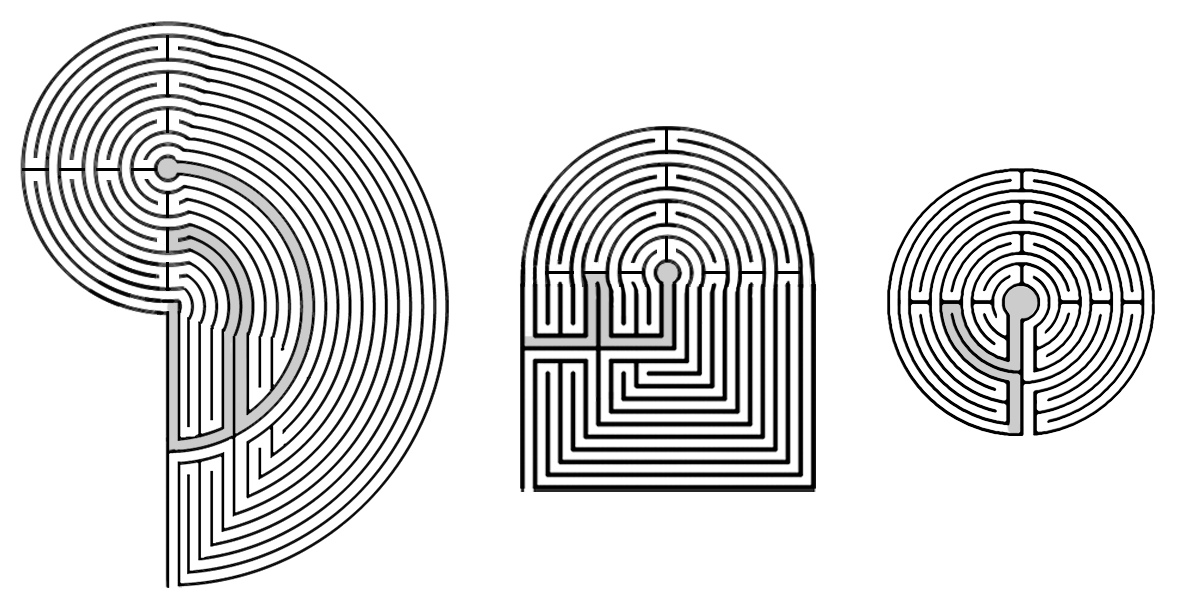

Embedding a medieval labyrinth (a straight-line version of the pattern popularised at Chartres Cathedral, minus its rosette and lunettes) within a Jericho’s seed is not too different to the previous steps:

- Create a rectangular version of the labyrinth;*

- Add an extra exit path, straight from centre to outside;

- Rotate it 90° clockwise, so that our exit path from 2. links to the Jericho’s centre, and our entrance path will double as the Jericho’s entrance. (Thus, we create the CD of this Jericho labyrinth.)

* Note also we must compensate for the convention of drawing a medieval labyrinth with its entrance in the left half of the pattern; for point 3. to work, we must flip it so the entrance is in its right half (Figure 9).

Now, we could tidy the pattern further to create vertically stacked elements around the south axis, rather than letting Figure 9’s elements fully flow from left to right (as in Figure 7’s inset box)...but such tidying is not a mandatory step and will be omitted this time, so we can keep an eye on our medieval labyrinth in its recognisable form. We’ll need to!

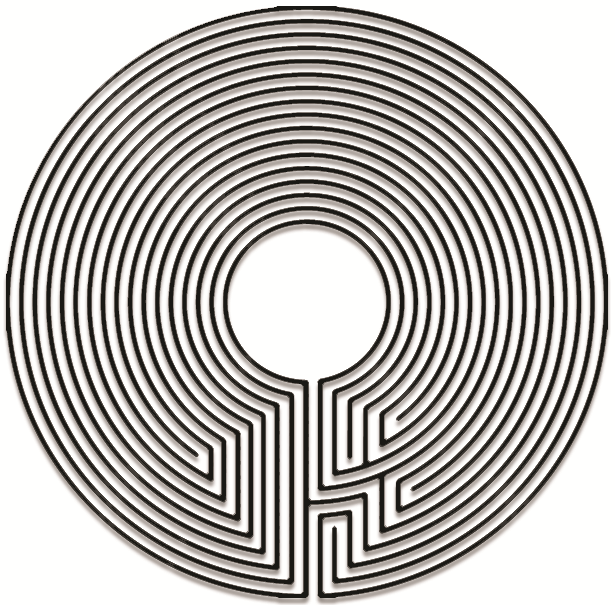

As noted, our rotated, squared-off medieval with two paths to its centre is now a functioning CD in our Jericho labyrinth, and once we have laid it over the waiting circuits and brought it around into self-enclosing form, we have our Jericho-medieval (Figure 10). Note how this resultant labyrinth has two axes; one at 12 o’clock (comprised of what would be, in a normal right-way-up Chartres, its west and east axes, now both merged at the point where they would have reached over to the centre into one single stream) – and then the busy, some would say hellish, arrangement of the Jericho’s 6 o’clock axis. Hellish it may be... but looking closely, you’ll recognise our medieval labyrinth’s spread there, as if reflected through carnival mirrors.

Two-Centred Jerichos

It must be said that these aren’t especially attractive labyrinths, seasoned as we are by conventional patterns’ appearances: in these, the south axes are strongly asymmetrical (not even pseudo-symmetrical), plus their large circuit-spans (16 and 24 respectively) make impractical many ‘standard’ applications we apply to seven- and eleven-circuit labyrinths.

But I was conscious of thinking little of the basic K227 Jericho, until I laid one on the lawn to walk for a few evenings. Then, experientially, I discovered that this pattern offered a succinct education in the fundamentals of labyrinth design; you meet stacked rebound, circle, radial, single rebound, and meander rapidly in those compact six circuits between entrance and centre. Expecting a yawn-fest, I received the opposite, so with our two new creations here I wasn’t deterred by appearance and carried on.

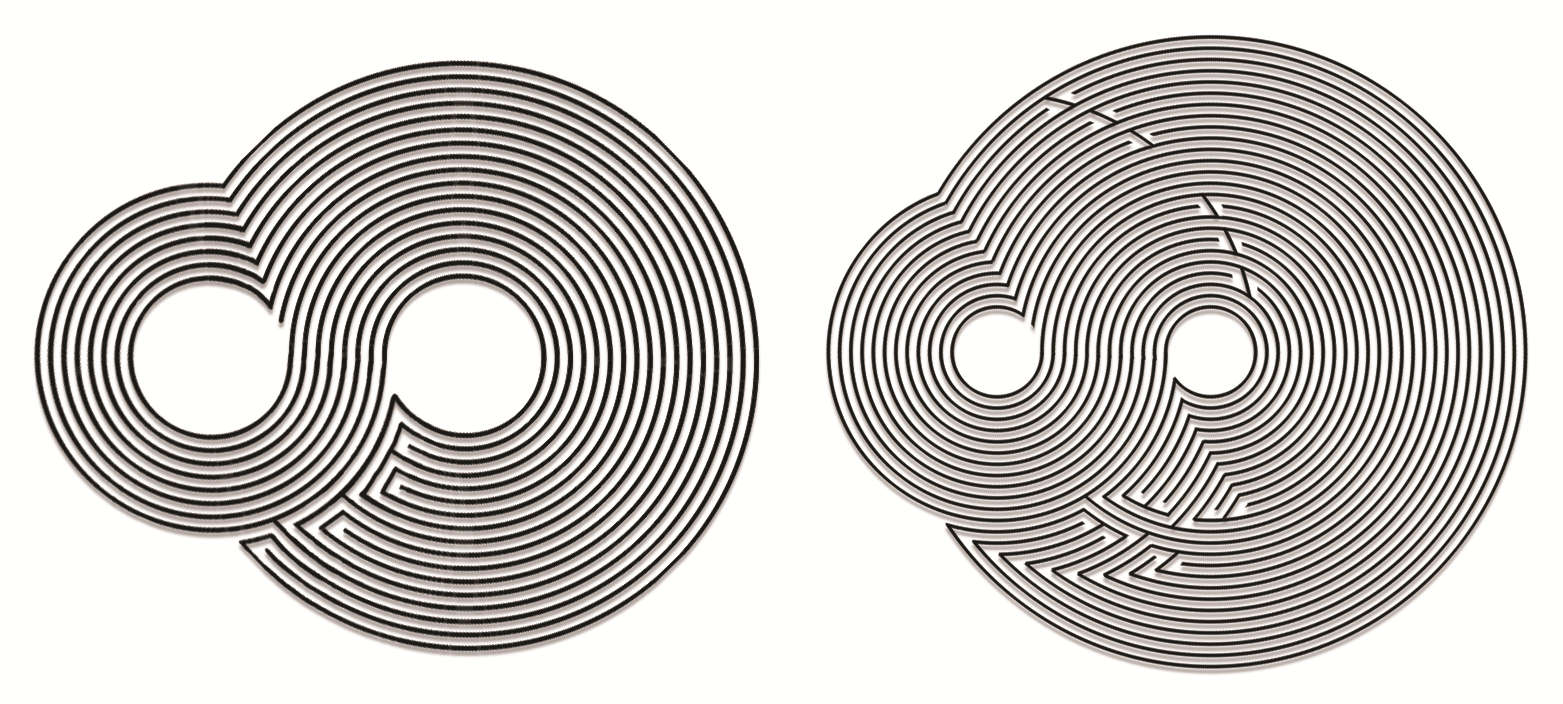

For we haven’t yet achieved our goal of embedding a true labyrinth within a labyrinth. The centres of our hidden labyrinths (that tilted 4FC, and medieval) are now swept to the left of our Jerichos’ south axes, slimmed to U-turns (recall Figure 8’s background labyrinth) and almost hidden beneath a geometrical rug. Can we restore those hidden centres to their original prominence?

The simplest approach to drawing attention to these secondary centres is to inflate them in situ. This forms dual-centred labyrinths which look quirky and odd, like vinyl LPs from another dimension (Figure 11):

But those secondary centres still have two paths leading in and out of them (like vascular hearts); to hold court within a true labyrinth, each should have one path alone to its centre, that glorified ‘dead end’ at the complex’s heart.

Achieving this creates a surprising outcome, which I’ll demonstrate with the Jericho-medieval; the same actions affect the Jericho-classical.

- Let’s first remove one of the two pathways leading into Centre 2, so we’re left with just one access to the centre. Since a pathway links Centre 1 and Centre 2 (shown in black, Figure 12 left) we can remove that pathway; this (Figure 12, right, in grey) allows the path around that erased path to ‘close in’, filling the void our excision has caused.

- Next let’s relocate Centre 2 from its drunken slump to one side, to sit within the overall pattern’s vertical axis. Figure 13 relocates Centre 2 and its neighbouring circuits so that their axes (from that hidden medieval pattern) also move and rotate 90° clockwise with Centre 2. We move from teardrop shape, to keyhole.

- Finally we correct the entrance point of the main labyrinth and its attendance flanking stacked rebounds and enveloping meander turns, so that instead of pointing left, they sit near the parent labyrinth’s base where we’d expect to find them. Once we rotate this section 90° anticlockwise, we face the south axis of the familiar medieval labyrinth. Admittedly its entrance is on the right, from the adjustment made earlier to create a CD serving our Jericho labyrinth’s directional flow. But aside from this - like the reveal-shot at a whodunnit’s climax - we face a familiar medieval labyrinth.

Conclusion

Extracting the inner labyrinth, it absorbs its parent. For the same happens with our Jericho 4FC, in the above steps: it unfolds to finally unmask as our familiar classical labyrinth.

Thus we can say that this process will extricate a proto-labyrinth (that is, a labyrinth having two entrances to its centre, and whose compression diagram has been rotated 90° clockwise to function as south axis within a parent labyrinth) from within the south axis of a Jericho labyrinth...if one was there to begin with. That is, of course, a mammoth ‘if’...but I nonetheless found this to be an interesting property of this slim sub-set of labyrinths. So long as double-pathways are injected into that proto-labyrinth’s centre, it will do this party trick; nor is self-reflectivity (e.g. mirroring of halves, around the CD’s centre part) required – as in Figure 14, extraction of labyrinth from Jericho seed occurs even if that resultant pattern is without internal symmetry.

Wide application? No. A must for the retreat centre? Er, no. But fun nonetheless; K227 offers a curious geometrical journey within the winding walls of their changing forms, and I encourage readers (if this is new to them) to play with this themselves.

Works cited:

- Figure 1 - Jericho as a labyrinth from the Farhi Bible; Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jericho_Walls,_Farhi_Bible,_Codex_Sassoon_368.jpg accessed 30/07/23.

- Bord, Janet. Mazes and Labyrinths of the World. Latimer. 1976.

- Kern, Hermann. Saward, J; Ferré, R (trans). Through the Labyrinth: Designs and Meanings over 5000 Years. Prestel. 2000.

- Saward, Jeff. Labyrinths and Mazes: A Complete Guide to Magical Paths of the World. Gaia. 2003.

Footnotes:

- These three are K225, K227, K229; Kn refers to figures from the 2000 English language edition. If you have the 1999 German edition, see K221, K223, K225.

- This incongruence lessens if we reflect that if we witness this labyrinth-city intact and complete, then we must be partaking of one of those first six encirclements; for on the seventh Jericho fell, and we would only see fragments of our labyrinth.

- Kern defines this as described: a path without intersections, continually changing direction, filling the space within its periphery, leading you past the centre repeatedly, ending at the centre and the sole exit route.